The workplace, once a stereotypical stuffy cubicle inside of a larger brick cubicle, has garnered much attention over the past couple of years.

In fact, so many progressive workplace improvements have been made over the last decade that now some mythical bubbles are beginning to pop. For example, while the open concept workplace may actually lead to a reduction in productivity, and not everyone wants or needs a standing desk. However, without attempting alternative approaches to workspace design, there would never have been a way to understand what works and what does not. Well, maybe there is but we just don’t know about it…yet.

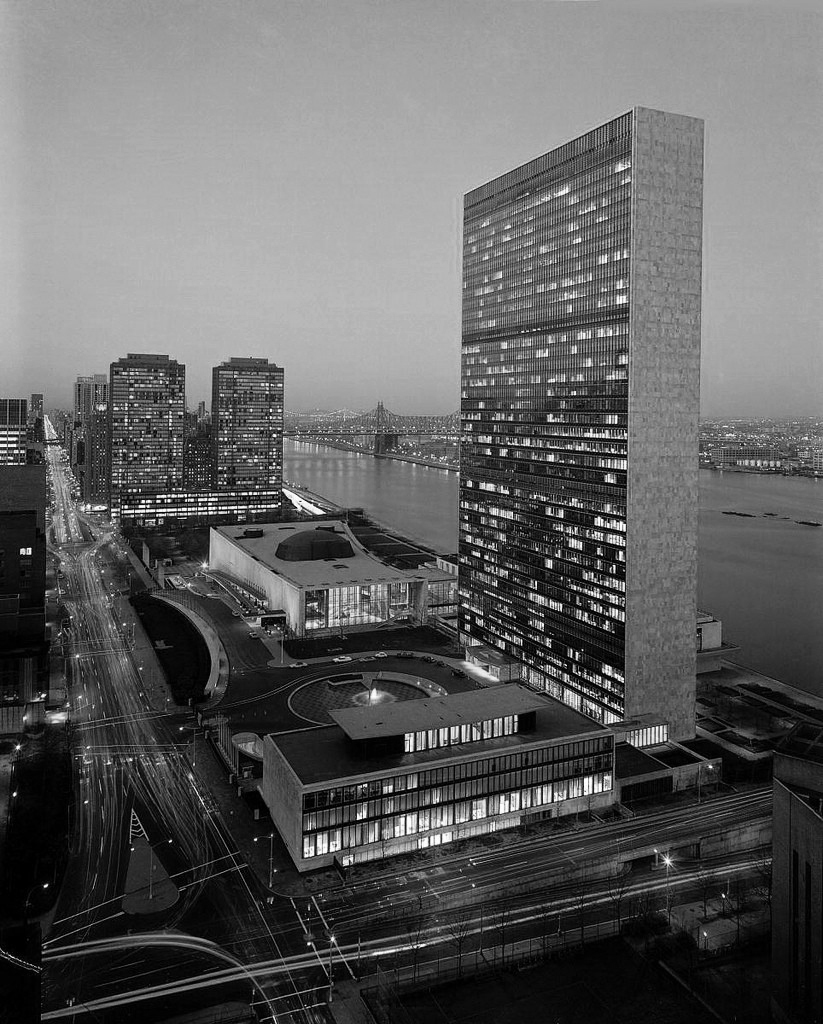

Founded in 2010, WeWork builds shared offices with a mission to create community spaces. A recent Bloomberg Businessweek article detailed the ways that WeWork has been collecting and analyzing information about how people move and operate within the workplace with the mission of using buildings more efficiently. WeWork recently implemented devices as a test bed in their own office headquarters, in San Francisco, to better understand how and when space is used.

Enabled by a recently acquired data software company, Euclid, WeWork located thermal sensors under conference room tables to detect how many people are in a room, at any given time. WeWork also maps cellphone data to understand where people spend their time both physically by location and digitally through phone usage. These various tools are not intended to target individual employees, rather they help WeWork understand how people and buildings respond to work environments on a large scale. With the relevant data, workspaces can adapt to fit employers needs for productivity and the environment’s needs for buildings to be energy efficient. Employees sport tee shirts that read, “Bldgs = Data.”

WeWork is right…buildings do equal data. We can not change the things we do not see. As a society that relies heavily on the scientific method, we still need hard evidence to pinpoint variables that must change for more productive, and frankly, practical solutions. The proper tools are not quite readily available to gather building data. WeWork will use their research to advise on ways to improve energy efficiency and the health, productivity, and well-being of a building’s occupants.

WeWork’s data begins to demonstrate where resources are wasted. This information is key to understanding how to preserve energy for our planet and, ultimately, for ourselves. If we study how we work and spend our time then perhaps we can get closer to a solution to the things that reduce our quality of life. Perhaps we can structure our lives and our buildings to meet our human needs.

Buildings equal data, and humans do too.

Every Move You Make, WeWork Will Be Watching You, Bloomberg Businessweek

Written for FutureAir By Mollie Wodenshek

Image Credit: Inkee Wang