Design “Intraspective” at the Pompidou Center in Paris from April 12 – July 3, 2017, is a must see, while work continues on Lovegrove’s next venture: Re-imagining indoor air.

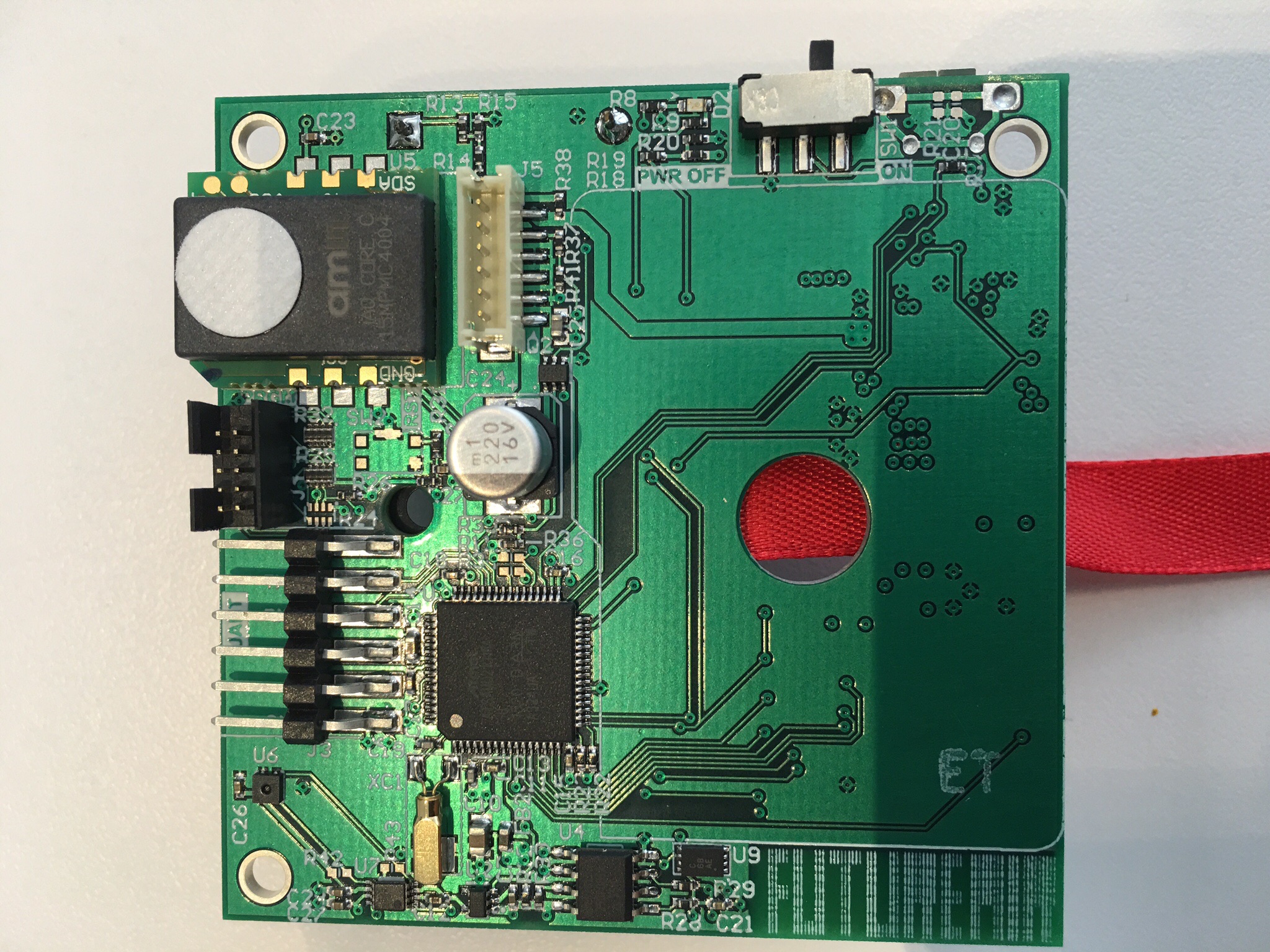

FutureAir, established in New York in 2014 by Simone Rothman and Ross Lovegrove, along with a team of scientists from Harvard, MIT and Columbia, sets out to provide increased awareness, highly innovative, smart-control applications and actionable products to monitor and deliver comfort and purity as well as energy efficiency for indoor air.

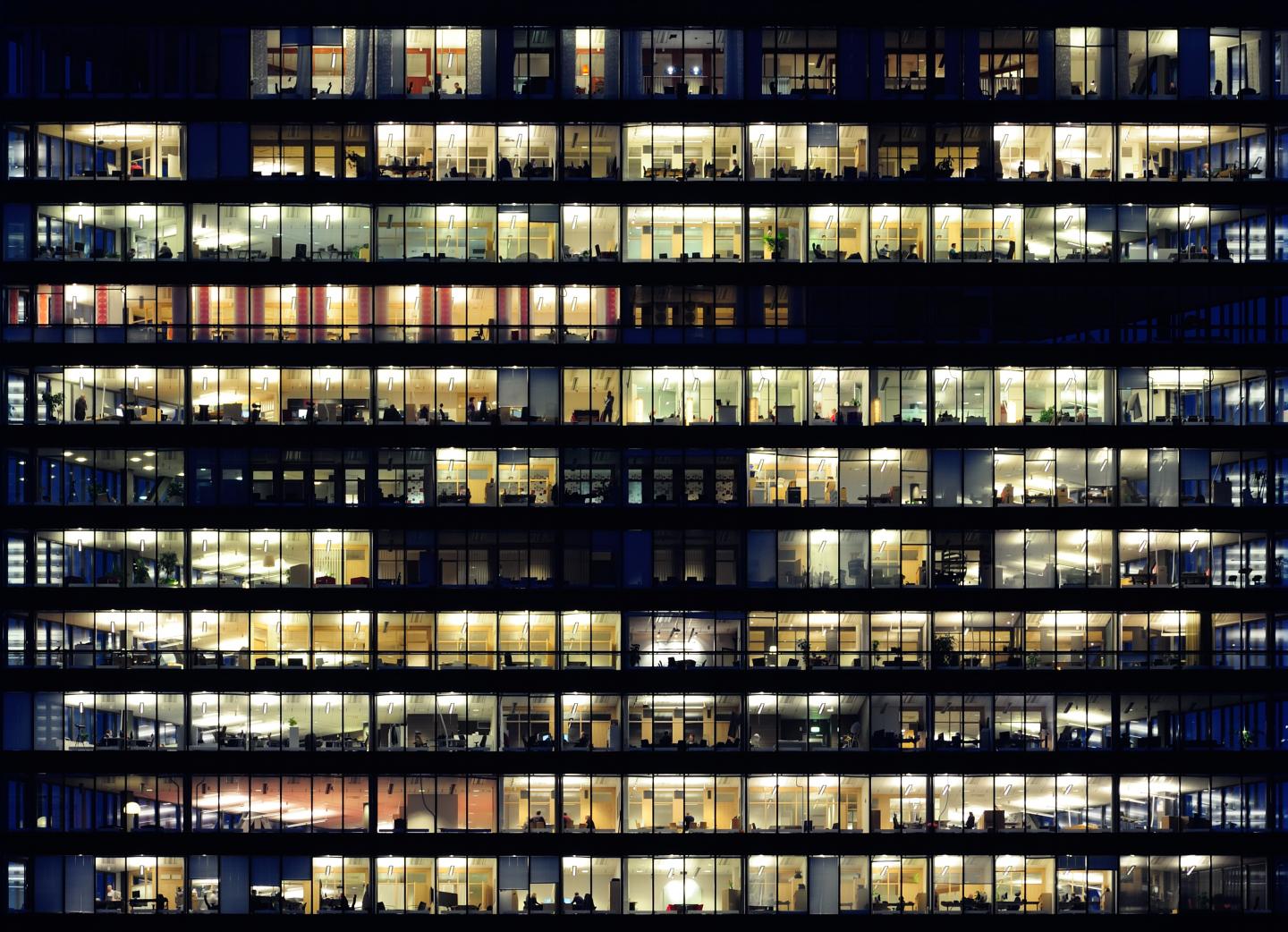

As the go-to platform for 21st century air-conditioning, FutureAir brings new awareness to the critical issue of indoor air pollution and its effect on health, comfort, productivity and general wellbeing. Sophisticated and affordable sensor technology developed by FutureAir, identifies harmful gas emissions and dust particulates, while monitoring room temperature and humidity to provide optimal thermal or “real-feel” indoor air comfort for home, school and office as well as in hotels and hospitals. Additionally FutureAir products, enabled with IoT device-to-device communication, regulate excessive energy output and “cooling waste” to reduce overconsumption and greenhouse gases emissions into our atmosphere.

The sleek Ross Lovegrove biomimetic designs for FutureAir products create a new standard for an industry sorely lacking in aesthetics. His late-career emphasis on Convergent Design, which combines emerging technology with new materials, is particularly evident in Lovegrove’s new designs for FutureAir. His organic, earth-centric works are inspired by the logic and beauty of nature mixed with social and environmental consciousness. “This idea of Convergence”, Lovegrove explains, “is an inevitability in this day and age, when we are looking for a new model of industrialization”. “Design will become more bespoke as we make only what we need and design’s beauty and logic creep in as ecology and as evolutionary. More and more designers will be asked to do something useful, to do something relevant.”

The future of quality air and the optimal indoor environment has found its designer. Ross Lovegrove…now partnering with science to evolve the way we breathe and live.

Photo credit: Andrew Bordwin