The Coronavirus pandemic has taken our world by storm, and it is our responsibility to continue to examine the forces at work that lead to unforeseen harm.

As our “normal” life has come to a halt the invisibility cloak has been lifted. We now see the individuals most at risk, we now see the areas with the most fraught medical infrastructure and their population demographics, we now see those workers deemed essential, we see the people that uphold our daily lives. We also see that visibility does not beget equality, and the distance between visibility and equality is work.

A study from the Center for Disease Control released on April 8, 2020, details how 33% of COVID-19 hospitalized patients are African American descent and the black demographic accounts for 13% of the U.S. population. In comparison, the white demographic, which accounts for 76% of the U.S. population, made up 45% of COVID-19 hospitalizations [NPR]. Evidently, the African American community is disproportionately affected by coronavirus.

Essential workers are required to continue working at no additional compensation for the added risk of contracting coronavirus. Many of these workers are paid minimum wage. The Trump administration recently suggested cutting wages of foreign guest workers on U.S. farms in order to assist the agriculture industry – an industry that received a $9.5 billion disaster aid relief package [Common Dreams]. Vulnerable workers are deemed essential and undercut in one fell swoop.

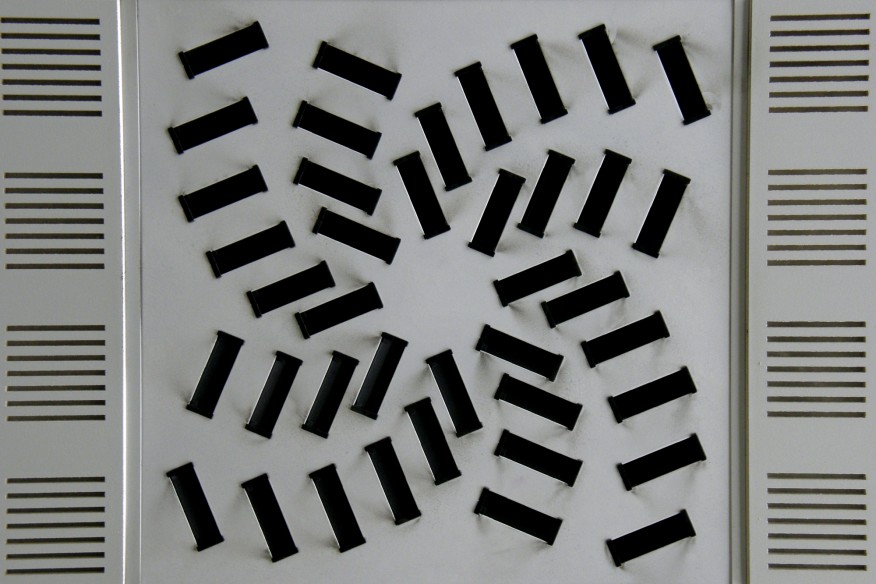

The New York Times detailed findings from a Harvard study in which higher rates of outdoor air pollution are associated with higher rates of hospitalization from COVID-19. Communities with high rates of PM 2.5 are at greater risk of illness. Those areas with the highest rates of pollution are also home to some of the most vulnerable communities. In New York City, areas of Queens, with numerous polluting power plants, have been hit hardest by the coronavirus, which is home to dense immigrant communities.

How have we played a role in creating these realities?

The evidence goes on. There are countless examples of injustice and inequality throughout our ‘normal’ daily lives, but on any other day, we choose ignorance. Coronavirus has exposed our fraught democratic system and shined a light on the overlooked and marginalized communities within that system. The evidence is more potent and direr than ever, and we must choose to see the forces of inequality, acknowledge the disenfranchised, and we must unlearn ingrained and inherited systems of inequality.

In these trying times, we may not have all the solutions…or any solutions at all. But at this moment, FutureAir is looking for the bright side – read about it here.

Aubrey, Allison, and Joe Neel. “CDC Hospital Data Point To Racial Disparity In COVID-19 Cases.” NPR, NPR, 8 Apr. 2020, www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/04/08/830030932/cdc-hospital-data-point-to-racial-disparity-in-covid-19-cases.

Friedman, Lisa. “New Research Links Air Pollution to Higher Coronavirus Death Rates.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 7 Apr. 2020, www.nytimes.com/2020/04/07/climate/air-pollution-coronavirus-covid.html?referringSource=articleShare.

Johnson, Jake. “’Bullying of Marginalized Workers’: Trump Moves to Slash Pay of Guest Farmworkers Amid Covid-19 Crisis.” Common Dreams, 11 Apr. 2020, www.commondreams.org/news/2020/04/11/bullying-marginalized-workers-trump-moves-slash-pay-guest-farmworkers-amid-covid-19.

Schuessler, Jennifer. “The Overlooked History of Women at Work.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 16 Jan. 2020, www.nytimes.com/2020/01/16/arts/design/womens-work-grolier-club.html.

Written by Mollie Wodenshek for FutureAir